|

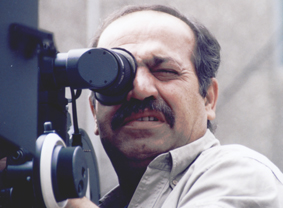

On Rasoul Molla-Qolipour (1956-2007)

Apocalypse Now

by Mehrzad Danesh

|

Iranian cinema is only one of the things that have been affected by the eight years of war between Iran and Iraq (1980-1988). The impact has led to the emergence of one of the most important genres of the Iranian films. Many Iranian filmmakers who make films in this genre have been present in the war fronts. They now make their observations into films. Ebrahim Hatami-Kia, Ahmad Reza Darvish and Kamal Tabrizi are some of these filmmakers. One of the most well-known of these filmmakers, Rasoul Molla-Qolipour passed away in March 2007 as a result of a heart attack. He was 51 years old. His death was widely reflected in the Iranian society. As well as being a director of war movies, he reflected contemporary social issues in his films. He was a controversial filmmaker and looked at the Iran-Iraq war from a different perspective. Due to his bitter approach he was nicknamed Oliver Stone of the Iranian cinema. This article, written on the occasion of his demise, enumerates the characteristics of his cinema. Iranian cinema is only one of the things that have been affected by the eight years of war between Iran and Iraq (1980-1988). The impact has led to the emergence of one of the most important genres of the Iranian films. Many Iranian filmmakers who make films in this genre have been present in the war fronts. They now make their observations into films. Ebrahim Hatami-Kia, Ahmad Reza Darvish and Kamal Tabrizi are some of these filmmakers. One of the most well-known of these filmmakers, Rasoul Molla-Qolipour passed away in March 2007 as a result of a heart attack. He was 51 years old. His death was widely reflected in the Iranian society. As well as being a director of war movies, he reflected contemporary social issues in his films. He was a controversial filmmaker and looked at the Iran-Iraq war from a different perspective. Due to his bitter approach he was nicknamed Oliver Stone of the Iranian cinema. This article, written on the occasion of his demise, enumerates the characteristics of his cinema.

Rasoul Molla-Qolipour was born in downtown Tehran in 1956 and spent his childhood and adolescence in poverty. As a young man, he was interested in the movies. Massoud Kimiaei’s Qaysar (1969) was one of his favorites. This was a film about an individual campaign against corruption. The theme appeared in some of Molla-Qolipour’s films later. The Islamic Revolution took place when he was young. At that time, he turned to amateur photography. As the war broke out, he went to the war zones as a professional photographer. Later, he made several documentary films on the war before beginning to film combat operations. He made his first short fiction film on the war in 1983. That was a 16-mm film about a young combatant who is responsible for water supply in part of the battlefront. The young hero dies thirsty. Molla-Qolipour made his first feature film Neynava in 1985. In all, he made 15 feature films in 22 years. He wrote the screenplay of all of those films.

His films are:

1. Neynava (1985): This 16-mm movie is about an old and a young soldier who have gone astray from their company and are wandering in the combat theater. One of them has been blinded by shrapnel and the other one is too weak. They go towards friendly forces thanks to what is known in religious culture as God’s assistance. This was more of a practice to enter the area of professional cinema. Otherwise it is full of structural mistakes. Critics likened a scene showing a combatant looking back at his broken down motorcycle to a similar scene with horses in western movies.

2. A Boat to the Beach (1986): This is a film about a number of soldiers commissioned to collect information from within the occupied city of Khorramshahr. This was a more professional-looking film than Neynava. Yet, it was overwhelmed by direct slogans.

3. Nocturnal Flight (1987): This is about an encircled battalion. The commander sends four men to seek reinforcement from the headquarters. Three of them are killed and the remaining one hardly manages to fulfil the mission. But it is too late as the commander, who has ventured into enemy forces to bring water for his men, is killed. Nocturnal Flight is one of the first Iranian war films with a local flavor. For the first time in this genre, this film attached more importance to the soldiers’ emotional situation than shootings and explosions. It is a clear manifestation of the first signs of Molla-Qolipour’s creativity.

4. Horizon (1989): This film is about a group of Iranian divers who embark on a mission to destroy an enemy naval platform. Many of them are killed in the course of the operation but finally the operation is successful thanks to sacrifices made by the divers. Many who had liked Nocturnal Flight were surprised by this imitation of western war movies. Molla-Qolipour, however, wanted to show his ability in directing exciting explosive and kinetic scenes. Horizon was thus a well-made movie with its own special meaning.

5. Majnoon (1991): The first film by Molla-Qolipour about a subject other than the war is about a poor ailing man who becomes mercenary to a terrorist in order to meet his requirements. He plants a bomb in an urban area but later changes his mind and defuses the bomb and this causes a violent row between the man and his employer. Majnoon is a bitter and violent film that has been made two years after the end of the war. This was a biting hint to the situation of former combatants who had lost their cause and were dragged into violent behavior. Majnoon was a good social drama with chaotic and nervous final scenes.

6. Lunar Eclipse (1993): This film is about a young man who becomes involved in the emotional and financial problems of a delinquent family. He tries to help a woman in this family who seems to be less corrupt. Molla-Qolipour in this film reveals his interest in surrealism by blurring the boundaries between reality and metaphysics in this complicated story. The opening and finale are shot at a graveyard to reflect Molla-Qolipour’s bitterness. Molla-Qolipour himself has said that this film was an experiment toward a personal cinema.

7. Refugee (1995): A young couple, who were active against the Islamic Republic while living abroad, give up political activities before secretly returning to Iran where they are being chased by their former comrades and the Iranian intelligence forces at the same time. They meet a former combatant and seek refuge with him. The film has a humane approach towards those who had once acted against the government and casts a nostalgic look at the war. A scene in which we see the combatant’s room and his relics from the war is one of the most nostalgic parts of the film. 7. Refugee (1995): A young couple, who were active against the Islamic Republic while living abroad, give up political activities before secretly returning to Iran where they are being chased by their former comrades and the Iranian intelligence forces at the same time. They meet a former combatant and seek refuge with him. The film has a humane approach towards those who had once acted against the government and casts a nostalgic look at the war. A scene in which we see the combatant’s room and his relics from the war is one of the most nostalgic parts of the film.

8. Journey to Chazzabeh (1996): Many critics say this is Molla-Qolipour’s best film and a brilliant work in the Iranian war genre. A filmmaker and a composer go on location to find themselves overwhelmed by war-time memories. The filmmaker meets his dead friends and the composer finds out how he should compose the soundtrack. As the Iraqis attack, the two escape and once again, find themselves on location. But the filmmaker is no longer interested in making the film. This film also takes a nostalgic approach to the war but here the narrative structure dashes back and forth between the past and the present and subjective and objective worlds. It is one of the first Iranian films in which we see depiction of the ambience of a bitter defeat. This was another experiment for the director to play with time. He used this experiment in many of his later films, but none was as good as this one.

9. The Rescued (1996): This film is about a female relief worker who is carrying a war-wounded to the behind-the-line area. The Iraqis attack the convoy and only the woman and a paraplegic soldier are spared. While travelling alone and with difficulty, they are joined by an Iraqi officer. This is an anti-cliché in the Iranian war genre in which not only a woman is present at the battle zone, but a sympathetic light is shed on an Iraqi officer and even shows conflict among Iranian soldiers. There are no false heroes. The film looks for the beauty of human soul amidst the violence of war.

10. Help Me (1999): This is the story of a young vet doctor who becomes the victim of a wealthy cattle breeder’s rage. The doctor meets a young woman who wishes to travel abroad and work as a singer. The cattle breeder chases them but he dies in an accident and the couple move on. This is Molla-Qolipour’s worst movie as far as the story and structure are concerned. It marks a chaotic juncture of the director’s life.

11. Hiva (1999): A woman, whose husband has gone missing in the war, goes to look for him 15 years later. She needs to see his body in order to believe his death. The journey reviews the love affair between the couple through the letters they exchanged in the course of the war. Once again in this film, Molla-Qolipour plays with the concept of time and blurs the boundaries between subjective and objective realms. At the same time, he shows bitter flashbacks depicting encircled combatants at war. Like in The Rescued, in Hiva too, Molla-Qolipour is looking for beauty amidst violence.

12. The Afflicted Generation (2000): This episodic film is one of the social films directed by Molla-Qolipour. In every episode, the director depicts the bitterness of a certain period. The first episode is about a love affair between a nurse and a handicapped Qajar prince. The young man is to be blinded because he has given away a family secret. The second episode shows the nurse a few years later when she has to mug a poor taxi driver to get the money that is needed for her daughter’s medical treatment. At the end, she dies in an accident. The third story takes place in modern times. The nurse’s daughter is now a member of a delinquent gang which is being busted by the police. The film, especially the second episode which is rich in symbolism, is one of the best works directed by Molla-Qolipour.

13. The Poisonous Mushroom (2002): This film is another look at former combatants who are now fighting the perpetrators of social injustice. The story of the film is about manager of a construction company, a former combatant, who is now fighting the board of directors and stockholders over illegal profits. One of his former comrades is at a mental hospital. The manager and the patient decide to fight the corrupt capitalists. They kill them before their own death. This is one of the bitterest films Molla-Qolipour has ever made. It is full of violent scenes including drug injection, people burning themselves and mental patients in epileptic seizure.

14. The Paternal Farm (2005): This is another return to the war but from a subjective point of view. A successful novelist who writes stories on the war is invited to deliver a speech at a former battle front. On his way, he finds the soul of his wife and children who had been killed in a missile attack during the war. The journey is then turned into a search for an answer to the question: Why did we fight? The film portrays nightmare-like pictures of the war, but it is devoid of bitterness as the author finds an answer to his question and is convinced that he had defended his country and family. This is the fourth film in which Molla-Qolipour breaks the time barrier between two different worlds.

15. M for Mother (2007): A young pregnant woman, a music teacher, who has been chemically wounded many years ago when she was a relief worker in the battlefront, is told by her doctor that her baby may be suffering from abnormalities. Her husband, a diplomat, wants an abortion but the woman refuses to undergo an operation and the man leaves her. She rears the child with much difficulty and teaches him to play the violin. A few years later, the woman is diagnosed with cancer as a consequence of exposure to chemical weapons. The husband returns from a long mission abroad to find his growing son performing in a concert despite his physical disability. At the same time, the woman dies at hospital. M for Mother is a passionate melodrama that was welcomed by the Iranian audience. Some viewers even fainted at movie theaters. The leading actress was criticized for over-sensationalization.

Shortly after the screening of M for Mother, Rasoul Molla-Qolipour died. He was preparing to make a documentary on the third Shiite Imam, Imam Hossein. Molla-Qolipour always wanted to bewilder his audience. This time, he did the same with his sudden death. Molla-Qolipour’s cinema had its own special characteristics. These characteristics made his films stand out in the eyes of the film critics. Some of the characteristics are:

1. Narrative structure: Before Journey to Chazzabeh, Molla-Qolipour’s films had a linear narrative structure. There were no signs of any interplay between the past and the present and the subjective and objective worlds. But this barrier was crossed many times in his later films. He had said in an interview with Film monthly: “I am fascinated with the idea of free flow of mind. That is a world I am in love with. I always have a longing for better situations. When I cannot get there, I seek help from my mind. Everything could be easily sorted out there. You could even destroy what looks pretty solid.” In Journey to Chazzabeh two individuals belonging to the present, share the agony of the people who lived ten years before that. A combatant talks to his son in the present time over a mobile phone and finds out through him about his own death. This is an example of how human perception expands in a timeline. The same experiment was repeated in Hiva with a love theme. The couple in love pass through the labyrinth of time to get together against their doomed destiny. In this film, women found the status they deserved in a masculine cinema. By breaking the time barrier, women could share the joys rather than the sorrow of their husbands. The same structure was handled in a surrealistic way in The Paternal Farm. The protagonist constantly dashes between the past and present and imagination and reality to the point that the boundaries between them are blurred. One of the best scenes in this film is the one in which the protagonist crosses the street to buy beverages for his family but instead of the drink shop he sees a wartime teahouse. Behind him, however, lies the present. The delicate visual technique used by Molla-Qolipour is one of the upsides of this film.

2. The biting bitterness: Before turning to filmmaking, Molla-Qolipour was a war photographer who recorded the violent scenes of the war. This background has left an impact on the way he looks at the world. His own portrait in some of his interviews and comments was one of a touchy person. Many were surprised to find after his death that he was in fact a man with a lively spirit. The most beautiful parts of Molla-Qolipour’s films are those that deal with defeat, destruction and death. His attractive characters are usually entangled in a doomed situation and await death. He was a master of creating apocalyptic scenes. The opening scene of The Poisonous Mushroom in which we see a combatant running in slow motion among the rubbles or the sense of defeat in the gathering of combatants in Journey to Chazzabeh or the suffocating scene of encircled Iranians in Hiva or the nocturnal attack scene in which confused combatants run aimlessly for their life are among these scenes. This bitterness is even more biting in Molla-Qolipour’s social films. In these films, he depicts individuals who are being crushed under social pressures. Sometimes this portrayal becomes chaotic like Help Me. In his last film, M for Mother, the main character has to face a variety of difficulties in order to give an opportunity to the dramatic violence of the film and make the viewer weep: a disabled child, poverty, a disloyal husband, cancer, mother’s death, unemployment, medicine smuggling, smugglers’ attempt to sexually abuse her, her child’s suicide, and so on.

3. Spiritual effects: In spite of this disappointing bitterness, Molla-Qolipour was influenced by his religious beliefs and this is evident from the religious signs he used in his films. In some of his films, there are recurrent references to religious stories. In the Nocturnal Flight the combatants’ thirst is reminiscent of the story of Imam Hossein (the third Imam of Shiite Muslims) and his brother Hazrat Abbas who was martyred while trying to fetch water to the Imam’s camp. Many of dialogues in this film and The Poisonous Mushroom are quoted from the remarks of Imam Ali, the first Imam of Shiite Muslims. Sometimes even the narrative structure of Molla-Qolipour’s films has a religious connotation. The presence of spirits of the protagonists’ wife and children in the Paternal Farm or telepathy between a young girl and the combatant in the Poisonous Mushroom is supernatural. Molla-Qolipour had told the Film monthly in an interview that he had made Journey to Chazzabeh based on a suggestion made to him by his martyred comrade in a dream.

His last film, M for Mother is also full of religious signs. While he was writing the screenplay of this film, Molla-Qolipour’s mother died and the main character’s mother also dies in the middle of the film. He recurrently used a Quranic verse which is recited at times of death and loss: “Why you deny God’s blessings?” There are also references to other Quranic verses in this film. Meanwhile, there is also a Christian character in the film whose relationship with his child is reminiscent of ties between father and son in the Christian relationships.

[Page: 20]

|

|

|

|

|

President & Publisher

Massoud Mehrabi

Editors:

Sohrab Soori

Translators:

Behrouz Tourani

Sohrab Soori

Zohreh Khatibi

Contributors

Shahzad Rahmati

Saeed Ghotbizadeh

Advertisements

Mohammad Mohammadian

Art Director

Babak Kassiri

Ad Designers

Amir Kheirandish

Hossein Kheirandish

Correspondents

E.Emrani & M. Behraznia (Germany)

Mohammad Haghighat (France)

A. Movahed & M. Amini (Italy)

Robert Richter (Switzerland)

F. Shafaghi (Canada)

B. Pakzad (UAE)

H. Rasti (Japan)

Print Supervisors

Ziba Press

Raavi Press

Blue Silver

Subscription & Advertising Sales

Address: 10, Sam St., Hafez Ave., TEHRAN, IRAN

Phone: +98 21 66722444

Fax: +98 21 66718871

info@film-magazine.com

Copyright: Film International

© All rights reserved,

2023, Film International

Quarterly Magazine (ISSN 1021-6510)

Editorial Office: 5th Floor, No. 12

Sam St., Hafez Ave., Tehran 11389, Iran

*

All articles represent views of their

authors and not necessarily

those of the editors.

|

|

|